The Placenta: Function and Health During Pregnancy

Cradle of Nutrition

- 4 minutes read

The Placenta: Nature’s Lifeline

The placenta is one of the most extraordinary organs in the human body. Forming only during pregnancy, it serves as a lifeline connecting mother and baby, delivering oxygen, nutrients, and hormones while removing waste products. It also provides immune protection and influences both maternal and fetal health long after birth.

Understanding placenta function and health during pregnancy is essential for every expectant mother. A healthy placenta is a key factor in proper fetal development and pregnancy outcomes.

How the Placenta Develops

The placenta begins forming shortly after fertilization. Once the fertilized egg implants into the uterine lining, specialized trophoblast cells invade the endometrium, creating the foundation of the placenta. By approximately the 12th week of pregnancy, the placenta is fully functional and begins producing hormones that sustain pregnancy and support fetal growth.

Week-by-Week Development Highlights:

- Weeks 1–2: Fertilization and implantation, trophoblasts begin forming placental structures.

- Weeks 3–5: Chorionic villi develop, creating the first interface between maternal and fetal blood.

- Weeks 6–8: Placental blood flow is established, oxygen and nutrients begin to reach the embryo.

- Weeks 9–12: The placenta fully takes over hormone production, and maternal-fetal circulation is optimized.

This dual circulation system — maternal and fetal — allows the placenta to efficiently exchange nutrients, oxygen, and waste while keeping maternal and fetal blood separate.

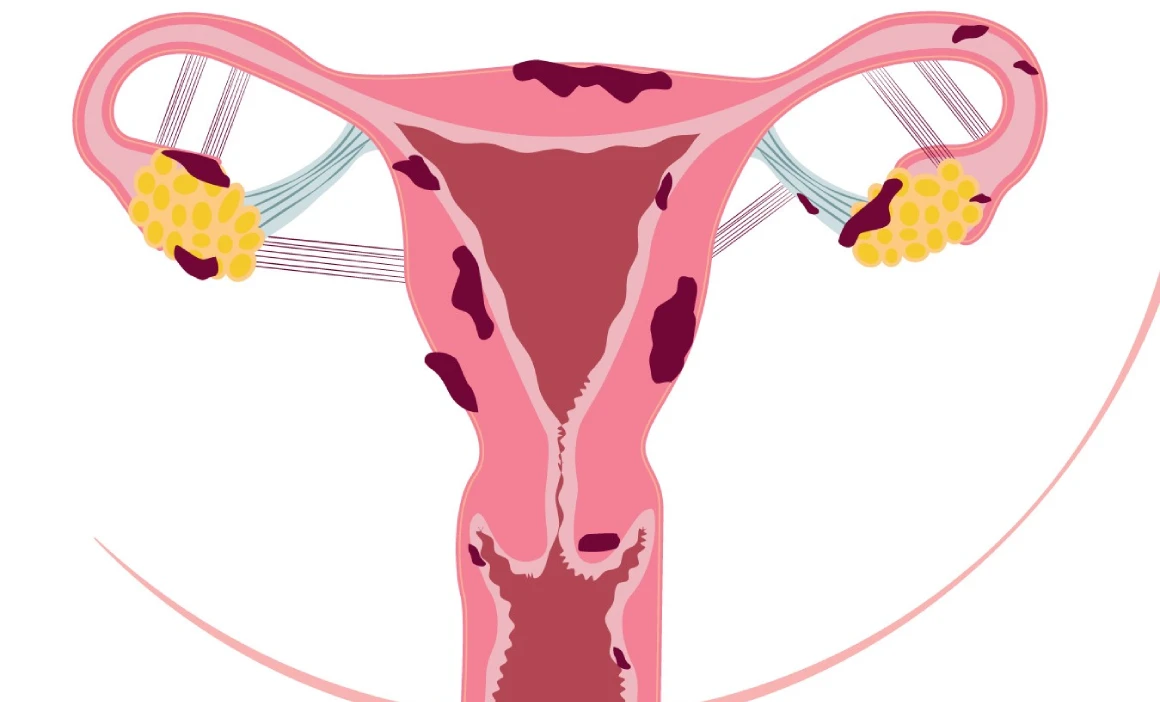

Placenta Structure: Layers and Sides

The placenta is a disc-shaped organ about 16–20 cm wide, 2–3 cm thick, and weighing 500–600 grams. It connects to the baby via the umbilical cord, which contains two arteries and one vein encased in protective Wharton’s jelly.

Two Distinct Sides:

- Fetal side: Smooth and shiny, facing the baby, where the umbilical cord attaches.

- Maternal side: Rough, dark red, divided into lobes called cotyledons, connects to the uterine wall for nutrient exchange.

Layers of the Placental Barrier:

- Syncytiotrophoblast: Outer layer in contact with maternal blood.

- Cytotrophoblast: Inner cellular layer aiding nutrient transfer.

- Basement membrane: Provides structural support and selective transport.

- Fetal capillary endothelium: Final barrier before blood enters fetal circulation.

This multilayered design allows oxygen, glucose, and antibodies to pass to the fetus while restricting harmful substances, offering a natural protective function.

The Placenta’s Functions

The placenta acts as multiple organs in one. It performs essential functions to support the baby and adapt the mother’s body to pregnancy.

1. Oxygen and Nutrient Transfer

The placenta transfers oxygen from mother to baby and removes carbon dioxide. Nutrients like glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids pass through the placental barrier, ensuring fetal growth.

2. Hormone Production

The placenta produces key hormones:

- hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin): Maintains early pregnancy.

- Progesterone: Maintains the uterine lining and prevents contractions.

- Estrogen: Promotes uterine and breast tissue growth.

- Human Placental Lactogen (hPL): Supports metabolism and prepares the body for lactation.

- Relaxin: Softens ligaments and cervix for labor.

3. Immune Protection

The placenta transfers maternal antibodies to the fetus, providing early immunity. It also prevents the maternal immune system from attacking the fetus, maintaining pregnancy tolerance.

4. Waste Removal

It removes urea, bilirubin, and other waste products from fetal blood, transferring them back to maternal circulation for elimination.

5. Regulation and Adaptation

Throughout pregnancy, the placenta adapts blood flow, nutrient delivery, and hormonal signals according to fetal needs, ensuring optimal development.

Placenta Health: Risks and Complications

A healthy placenta is critical for a safe pregnancy. Several conditions can compromise placental function:

Common Placental Disorders

- Placenta previa: Placenta partially or completely covers the cervix, may cause bleeding.

- Placental abruption: Early detachment of the placenta reduces oxygen supply to the fetus.

- Placenta accreta: Deep attachment to the uterine wall, creating delivery risks.

- Placental insufficiency: Insufficient oxygen or nutrients lead to growth restrictions.

Risk Factors

- Maternal age over 35

- High blood pressure or preeclampsia

- Smoking, alcohol, or drug use

- Previous cesarean section or uterine surgery

- Multiple pregnancies

High blood pressure and smoking are especially harmful. Hypertension can reduce blood flow, and smoking damages placental vessels, increasing the risk of complications like abruption or placenta previa.

Learn more in our detailed guides:

After Birth: The Placenta’s Journey

After delivery, the placenta completes its function. During the third stage of labor, it separates from the uterine wall and is expelled naturally. Healthcare professionals examine it to ensure it is intact, preventing complications like retained tissue.

Cultural Practices and Modern Science

Some cultures bury or honor the placenta as part of ritual practices. Others explore placenta encapsulation, though scientific evidence on its benefits is limited. Researchers study placental tissue for regenerative medicine and stem cell applications.

Long-Term Implications

Research shows that placenta function and health during pregnancy can affect both mother and child long-term:

- Poor placental function may increase maternal risk of cardiovascular disease later in life.

- Restricted placental growth can contribute to metabolic issues in children.

- Placental health may influence neurodevelopment and immune system function.

The NIH Human Placenta Project is uncovering how this temporary organ leaves lasting biological impacts, making early care essential for lifelong health.

How to Support Placenta Health

- Maintain a balanced, nutrient-rich diet

- Avoid smoking, alcohol, and harmful substances

- Manage chronic conditions like hypertension

- Attend all prenatal checkups

- Follow medical guidance on pregnancy complications

- Engage in safe exercise and stress management practices

These strategies optimize placental function, supporting a healthy pregnancy and fetal development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main function of the placenta?

It connects mother and baby, providing oxygen, nutrients, and hormones, while removing waste.

When does the placenta become fully functional?

Around the 12th week of pregnancy.

Can lifestyle affect placenta health?

Yes. Nutrition, exercise, and avoiding smoking/alcohol significantly impact placental function.

What happens to the placenta after birth?

It is expelled during the third stage of labor and examined for completeness.

Is the placenta used in medical research?

Yes. Researchers study it for fetal development, immunology, and regenerative medicine.

By Erika Barabás

Sources:

- WHO — Maternal and Newborn Health: Placental Care and Complications

- NIH Human Placenta Project — The Placenta: Transient Organ, Lasting Influence

- Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2022)